| Gummiland Life | |||

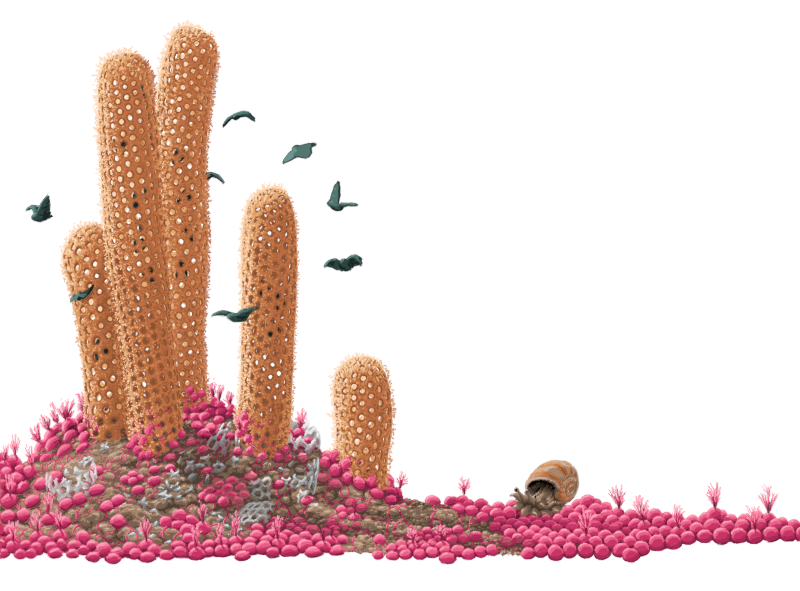

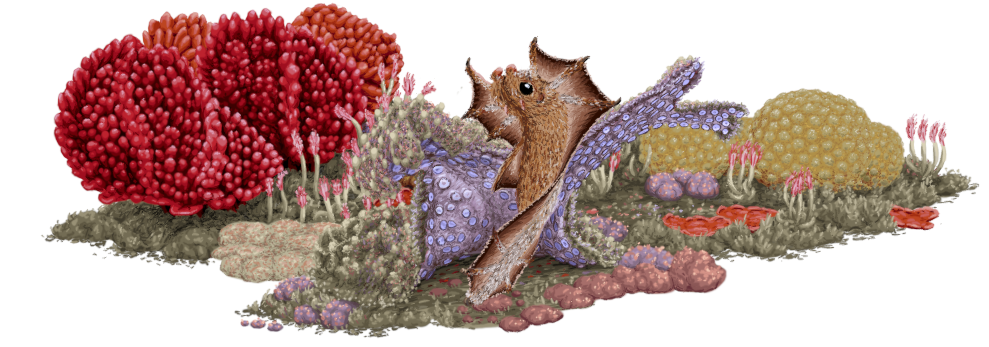

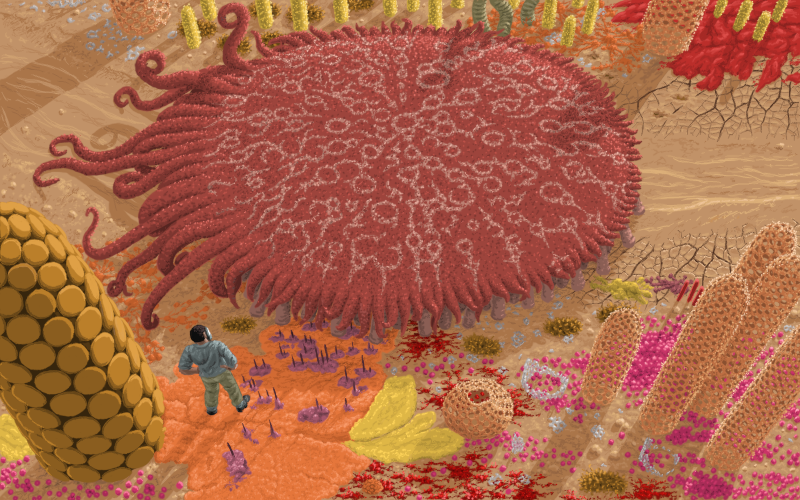

Few Humans have traveled to Gummiland and returned. One of the best known is explorer Jamal Dubois, whose accounts of his travels in the pre-Bump Gummi Expansion have become classics in the Verge. In this image, Dr. Dubois is seen traversing a shrume savanna and land reef. The native Gummiland atmosphere has a toxic level of carbon dioxide, necessitating breathe masks and scrubbers. Durable boots, rugged pants, and ankle wraps are recommended to protect against the defenses of bunkles and other cruds and oozes.

Few Humans have traveled to Gummiland and returned. One of the best known is explorer Jamal Dubois, whose accounts of his travels in the pre-Bump Gummi Expansion have become classics in the Verge. In this image, Dr. Dubois is seen traversing a shrume savanna and land reef. The native Gummiland atmosphere has a toxic level of carbon dioxide, necessitating breathe masks and scrubbers. Durable boots, rugged pants, and ankle wraps are recommended to protect against the defenses of bunkles and other cruds and oozes.

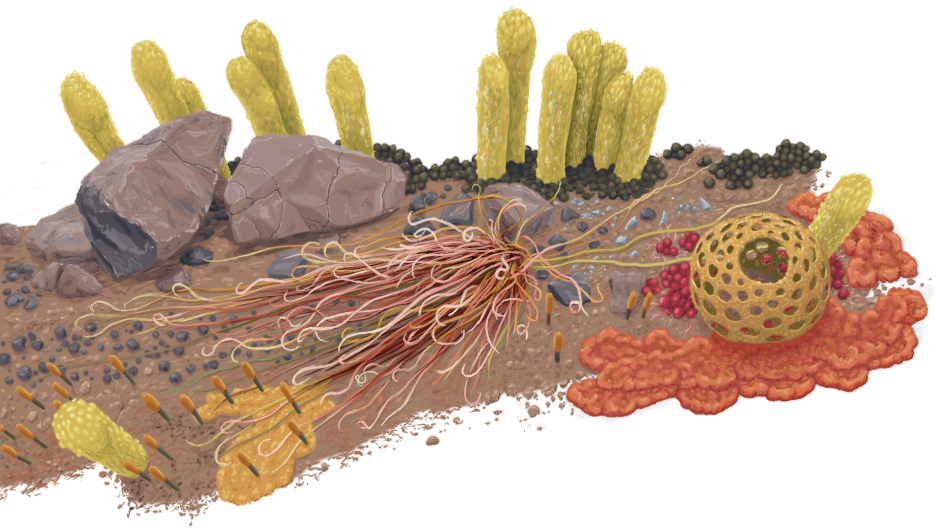

A given crud colony will expand and move around to find resources. They often have a patch of territory that they will vigorously defend. Colonies meeting each other are likely to fight, although it is common to find associations of different species of crud (or other organisms) living together symbiotically. Different species have evolved a wide variety of methods to defend themselves, including poisonous tissues, oozing toxic, sticky, and/or corrosive secretions, firing venomous barbs, releasing clouds of toxic spores, and even explosively bursting to blast competitors and predators with directed jets of scalding boiling water and foul toxic chemicals (similar to the method used by Earth's bombardier beetles). However, these adaptations are biologically expensive and lead to slower growth, such that many species simply out-compete their rivals by growing faster without any special defense.

Each tube is its own zooid, usually terminating in a suction end and a single simple eye. Although their visual aculity is not great, it is enough for them to detect looming threats or seek light or shade as needed. They'll use their suction end to adhere to surfaces and gather food and minerals. Mop tops are found in most environments, and come in sizes ranging from as small as a dandelion seed to larger than a beachball. They engage in various levels of heterotrophy, with some species content to gain almost all of their carbon and energy from light and air while others graze on sessile organisms and organic debris, parasitize other organisms, or even engage in predation.

Like mop tops, they don't have a specific orientation and as their tentacles pull them along they roll as they go. Spaghetti trappers may forage in the open, but retreat under rocks or wedge themselves into crevices or other hidden places to rest. The very largest species of spaghetti trapper will occasionally attack a sapient being. As a safety precaution, larger individuals should not be closely approached.

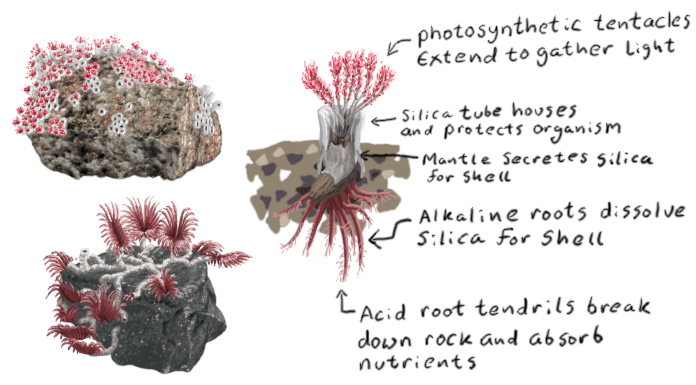

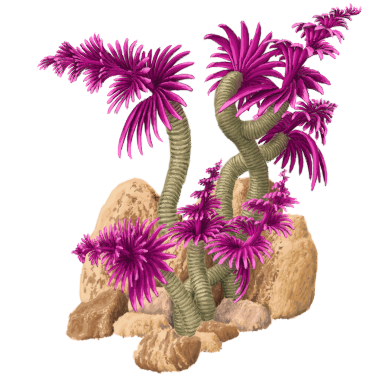

Many species of screw-feather tree exist, each adapted it its own particular niche that involves rock and soil type, climate, and light availability. Some grow as big as a pine or fir, others are mere shrubs. Different species use different photopigments, such that a multi-species forest of screw-feather trees can produce quite the visible spectacle. Because they do not compete for silica, screw-feather trees can grow alongside species that form silica shells where the geology is silica-constrained.

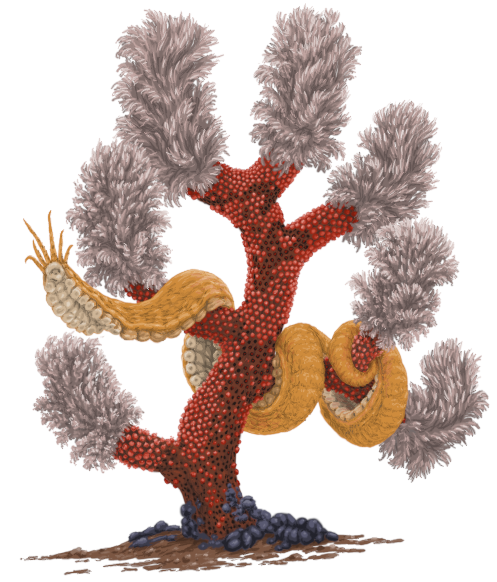

Many species of shrume have evolved a symbiotic relationship with certain varieties of crud. The shrume drops its waste and dead zooids from its living canopy. This feeds the crud, which grow around and on the tree. The crud, in turn, defends its shrume from other competitors. This includes attacking any rock fuzz that would otherwise grow as epiphytes on the trunk and branches, which would weaken the shrume's skeleton. Shrumes make up an important part of land reef ecosystems. As one of the larger sessile organisms of these regions, they often give the appearance of a savanna or woodland, with scattered shrumes dominating the landscape. Shrumes are preyed on by a variety of loopers and fuzz-rugs that can climb, glide, or fly into the canopy.

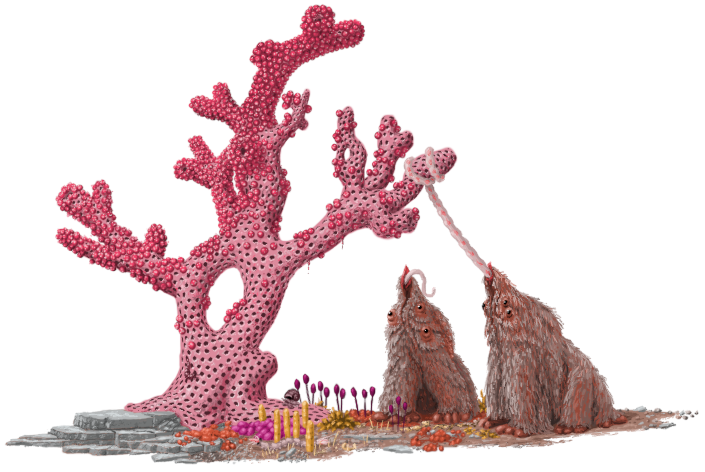

Puffing Bunkles: Puffing bunkles look like pink fleshy balls. They are a common variety of photoautotroph, detritovore, and filter feeder; and often blanket surfaces with their globular forms. The outer mantle of a bunkle is a tough, leathery surface that helps them resist predation. Bunkles do not make mineralized skeletons, and thus are not restricted to growing in places with skeleton-forming minerals. They do need the usual nitrate, phosphate, iron, and other fertilizers and benefit by consuming organic carbon, all of which they access by capturing small animals and by growing tube-like roots that burrow underground or snake across the surface. These roots are mobile, and can search around for new nutrients when they have exhausted previous supplies. In extremes, bunkles can slowly crawl to a new location. Some roots will typically seek out other bunkles in the colony, keeping contact and serving as a means of communication and exchange of water and nutrients. Bunkles can extend a feather-like structure to capture more light, sieve air plankton, or release pheremones or attractants for small mobile creatures. If bothered, they will retract their extremities back into their mantle for protection. If gravely threatened, they will release a puff of spores that cause irritation, pain to mucous membranes, rashes, and ulcers.

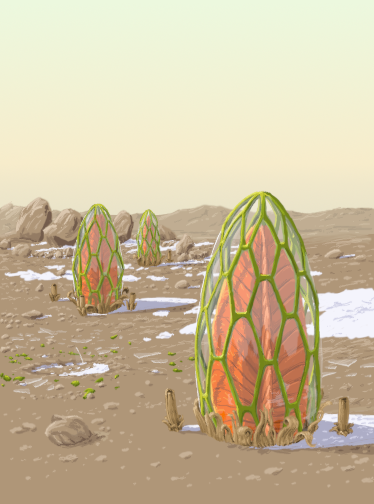

The illustrated species is called the bottle bush. The organism grows underground, sending up tube-like structures around its greenhouse bottle for respiration. The bottle, once formed, cannot be re-sized. Thus young bottle bushes grow with only the tip of the dome showing, and the dome is further extruded as the bush grows. The glass panels are originally covered by a layer that excretes the silica and the chalcedony framework, which is protected by a keratinized sheath. As the glass panel is fully formed, the growth tissue dies off and the keratin peels away. The photosynthesizing portion of the bottle bush is a single giant quilted succulent "leaf" with five-fold radial symmetry. The bottle protects the leaves from winds and weather, which are the usual factors that restrict leaves to smaller sizes in other organisms. The self-contained growth habit of the bottle bush allows them to store water in their fleshy "leaves" and underground body. In this way, the bush can survive in cold desert environments. They are also often found at high altitudes where they can get plenty of sunlight but have to endure cold temperatures. The underground body of the bottle bush is a blob of flesh that looks something like a shucked clam. It has tendrils that can unclog its breathing tubes and clean the glass of dust, grime, and slime. There are several varieties of predators that have evolved to break through the glass of bottle bushes to get the delicious flesh inside. One defense against this is that the glass is stressed so that while very sturdy, when it does shatter it breaks outward, potentially cutting the attacker. A broken window can be scabbed over, the scab eventually forms another layer of glass secreting tissue and creates a new pane. Once the pane is thick enough, the scab falls off.

The most feared death snails are the candy-stripe death snail and the ram's horn death snail (shown at right), which produce fast acting neurotoxins stored in large venom glands and which can hydraulically launch their tethered darts some distance. A mature candy-striper can hit targets up to a meter distant, while a particularly large ram's horn death snail was once found to have hit a target five meters away (although three meters is more typical for a mature adult). Gummis have evolved to innately recognise death snails and similar shapes. They can detect even camouflaged death snails in a cluttered background more rapidly than other objects. As a result, Gummis tend toward emotional reactions toward death snails, similar to that of Humans to serpents, which may manifest as fascination and admiration or which may take the form of phobia. Coiled shell motifs are common among Gummi religious art, Gummi mythology often features Gummi snails – often capable of speech and reasoning, often with magic powers, and often of monstrous size, form, and inclination. Gummis with a snail phobia are likely to be similarly freaked out by Earth gastropods and nautiluses.

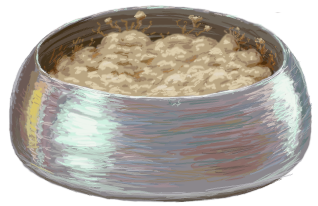

There are many varieties of pudding, some cultivated for their flavor, some for their cleaning ability, and some for their decorative properties (such as a pleasing aroma or growth into interesting shapes). Many Gummis get quite attached to their pudding colonies, and many colonies are kept in a family for generations. Shown is a food cultivar of pudding kept in a nacre bowl.

Pudding grubs grow quickly and reproduce rapidly. They are important sources of food for many predators. Indeed, without adequate predation, they can quickly explode in numbers until they grind entire land reefs down to sand. Pudding grubs are a significant part of Gummi cuisine. They take their name from commonly being eaten with Gummi pudding. Depsite their repulsive appearance, many Humans find them delicious!

The zooids in the tail of a mud rubber mostly lack legs and eyes. They are used for balance and fat storage. However, one of their primary uses is reproduction. Generally, the first one to three tail zooids are male; the rest are all female while the body zooids are neuter. When two mud rubbers mate, the male zooids inseminate the female zooids. These zooids carry the embryo as it develops, gradually being consumed by their offspring. Eventually, the female zooids fall off shortly before dying and giving birth. The mud rubber will then clone a string of new female zooids for another tail.

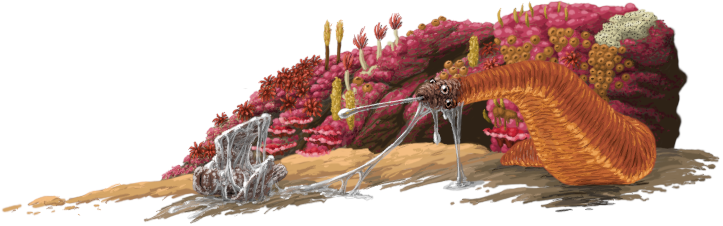

Mimic: Experts at camouflage, mimics are ambush predators that can adjust their color, texture, and shape to effortlessly and nearly instantly blend in to the background. Closely related to Gummis, they use their amorphous form to their advantage to appear as harmless natural features. A mimic can wait patiently for food to come by, or slowly creep up on unaware victims. Then, with a sudden pounce, the mimic will shoot out sucker-lined pseudopods to capture its prey, drag it back, and envelop it. The image above shows a mimic in mid lunge as it attacks a looper that ventured too close. One species of mimic has self-domesticated to life among the Gummis, living in their homes and helping with pest control. They make charming pets, appreciating affection and contact with their owners but largely content to take care of themselves.

The image shows a spitter that has captured a dappled wingding, hopelessly trapping the victim in a web of snot.

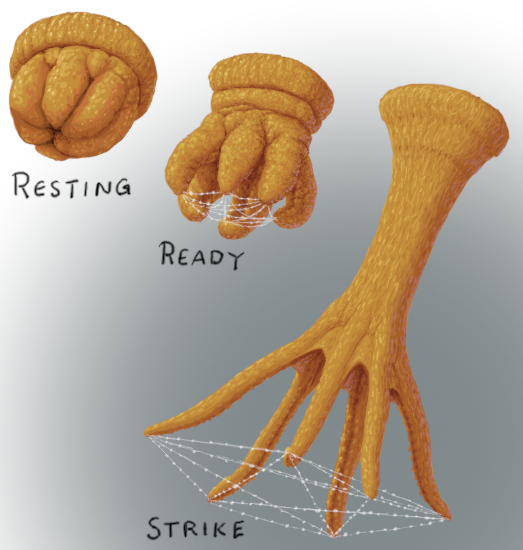

A netter can move slowly, crawling along with undulations of its adhesive disk. When hungry it will look for suitable ambush sites, ideally along a well-used game path or with structure that naturally funnels prey toward a choke point. After eating its fill, a netter will retreat to a sheltered site to digest. Netters are known to re-arrange litter and rocks to make barriers that guide prey toward their ambush site. Once a netter reaches a large enough size, it will seek a mate. Male and female reproductive zooids will be produced in large numbers. Once fertilized, the netter essentially begins to dissolve into writhing mass of new young. The juveniles feed off the tissues of their parent. When the parent has been fully consumed the young will have grown large enough size to catch prey on their own and they disperse to find their own place in the world. Most netters range in size from a sesame seed to a basketball. A few species grow large enough to occasionally be a threat to the sapient species of the verge. The most dangerous is the sunflower netter, which can grow as large as an ottoman footstool, has over twenty tentacle-arms, and can trap and consume prey as large as a Human (which will provide enough food to trigger reproduction and death).

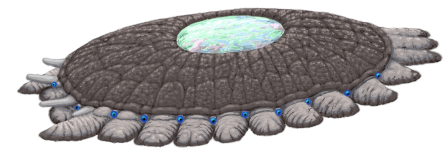

Fuzz rugs are named for the waving carpet of sensory tendrils that cover their edges and upper surface. They are flattened, amorphous masses that move via innumerable tube feet on their underside. These tube feet also pluck food items from the ground and deliver them to the fuzz rug's mouths.

Walking carpets may be solitary (as in the image shown), but often congregate into herds. These are commonly related organisms that travel together, with the oldest and wisest among them leading the group. During migrations, these family herds can merge into swarms thousands strong. Walking carpets are rather intelligent and curious animals. They often gather to investigate novel things or happenings in their environment. These animals will aggressively drive off perceived threats but are quite tolerant of beings that do not seem dangerous. The sapient species of the Verge can usually approach them closely and even engage in respectful contact. They will often allow themselves to be ridden, although passengers which are too rambunctious are likely to be grabbed with a tentacle and dropped on the ground. Those who are too pushy or ignore the carpet's signals that they are not feeling social or have had enough can be roughly pushed or even flung aside. Anyone who seems to be an actual danger to a herd is likely to be trampled and torn apart.

Hoovers amble about the landscape in large herds, plucking less-mobile food with their leg-trunks and swallowing it to pass down an esophageal tube in the trunk to the stomach vacuole. As amorphous animals, their number of leg-trunks varies, and they can stretch or contract to assume a shape best fitted to their foraging needs – whether stretching tall to feed at treetop level or as a compact lump with a long trunk feeding from a wide swath of ground around it so as to spend less energy moving around. Hoovers are in constant communication with others of their herd. They use rumbles and low hoots and trumpets as well as inflating their crests and using touch and body language. Their bodies are noticeably iridescent, a trait thought to allow them to visually keep track of each other.

Like most colonial animals, suckerbeasts have both male and female zooids. When impregnated, the female zooid will swell into a large sac containing thousands of eggs. After hatching, the young will remain near their parent for 8 to 15 megaseconds, being fed by secretions from the parent until they are large and skilled enough to hunt for themselves. In the image shown, an ambitious suckerbeast has caught a young hoover. It is unlikely to be able to fully capture such large and powerful prey, but if it can force the hoover to autotomize a limb in order to escape it could still obtain a sizeable meal.

Shown is the duster scrub, a common variety of polyp bush in semi-arid areas. Duster scrubs are characterized by their puffy terminal branch-ends used to spread gamates during the reproductive season. These puffs resemble the feather-dusters Humans used to use for cleaning, hence their common English name. Strangleconda: Stranglecondas are predatory, worm-shaped colonial animals. They consist of a double row of zooids, each with a suction pad used for feet. A durable leathery jacket covers their back, often studded with subdermal mineralized plates. Sensory tendrils project from the front end and (in many species) along the sides. Many grow to large sizes. They grapple their prey with their supply bodies and suction feet. Non-colonial victims can simply be squeezed to death; colonial animals may try to disassociate, allowing the strangleconda to pick off the individual zooids and consume them piece-wise.

If harrassed, many species of strangleconda will coil themselves into a ball with only their tough outer jacket exposed, hoping their attacker will not be able to get through their armor.

Lasso beasts amble about slowly on pillar-like pseudopods. When feeding or resting they look like large hairy cone-shaped lumps of fur. They have irregularly placed eyes around their body, typically concentrated near the lasso flinging orifice to provide binocular vision for accurate lasso placement. Lasso beasts are generally fairly placid creatures. If threatened, they gather together with the young and weak inside the group. Those on the perimiter will defend the group with stomps and kicks, and will grapple and dogpile larger threats.

The particular need for both iron and sulfate to build their skeleton means that goldbottles are restricted to patchy areas with the right geology. Where conditions favor them, they can be numerous. Outside of Gummiland, goldbottles are often found on San Agustín where mafic igneous rocks abut evaporite deposits. Goldbottles are popular ornamentals for gardens and potted displays throughout the Verge Republic and Gummi Space.

Different species of jack in the bottle are adapted to prey on a variety of Gummiland skeletinized photoautotrophes. Each species is usually specialized to a single species of host. Screw feather trees, shrume trees, toobs, polyp trees, and even rock fuzz have their own varieties of parasitoid. Some species of jack in the bottle even parastize other jack in the bottle species.

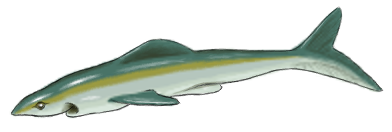

Gulper tubes are aquatic animals, nearly ubiquitous in aquatic environments. They swim about by gulping in water at their front end and expelling it from their rear. Most filter out plankton and marine detritus as the water passes through. Other, however, are predatory; engulfing smaller animals and digesting them. Those of the open water or deep sea tend to have gelatinous bodies to help them hide through transparency. More athletic and active gulper tubes, often dwelling in freshwater or near the sea floor, can be more muscular than gelatinous with opaque bodies camouflaged by pigmentation instead.

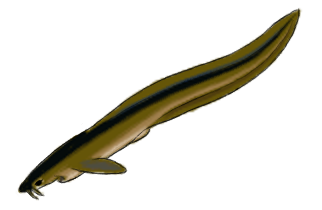

Loopers are monopods, albeit with finger like graspers near their head. At slow speeds, they move forward much like an inchworm or leech – hence their name. First they anchor their rear foot and reach their front section forward, which then grabs on allowing them to move the rear foot forward. At high speed, they hop in long bounds. Most species have a patagium stretching between their fingers and toes down their sides. During a hop, they splay their finger-toes wide and flatten their body top to bottom to give an aerodynamic surface. This allows them to maneuver while hopping and may add some range through gliding.

These animals are alert and wary, quick to flee at the slightest disturbance. Their high speed allows them to escape most predators if they have warning. Small loopers may retreat to burrows for shelter, larger species may take cover in brush or simply live in large herds and keep a sharp eye out in flat, open areas.

The bunkle muncher is an example of a species of looper. They are adapted to graze on puffing bunkles. Bunkle munchers are resistant to bunkle spores, allowing them to pop the bunkles without harm to themselves. When grazing a patch of bunkles, they are often surrounded by a wafting cloud of spores from their prey, squirting from around their oral disk and exhaled from their respiratory openings. This cloud deters predators, allowing the bunkle muncher to dine in peace.

When not eating puffing bunkles, bunkle munchers are more vulnerable and will be more alert and wary. They store a charge of bunkle spores for use in an emergency. If escape is not possible, they will exhale their stored spores at their attacker.

Puckle-loopers, or just puckles, are a commonly encountered species. These animals are arboreal browser-omnivores. Their sharp, curved claws help them hold on to the exoskeletons of various Gummiland "trees", while their elongated bodies better enable them to clamber among branches. Backward facing toes let them prop themselves upright on vertical surfaces. Like many loopers, they are agile gliders capable of leaping long distances between perches. The fur of some species is dramatically colored saturated shades of purple, red, orange, or yellow. While attention-grabbing in isolation, these colors help them to better blend in with the assorted pigments of the many varieties of Gummiland photoautotrophes. Puckles use their dextrous front grippers to select choice morsels for transfer to their oral disks. This can include exposed polyps, as well as equivalents of seeds (eggs) and fruits (fleshy nodules encasing digestion-resistant eggs). Not to mention the occasional Gummi slug or inattentive wingding. Puckles regularly cache large amounts of food for seasons of scarcity. Caches are often split up among many locations, so that if one is discovered the puckle will not starve. Puckles thus have excellent spatial memory to keep track of them all.

Puckles are prey for many different predators. Their main defense is their wariness, speed, and agility.

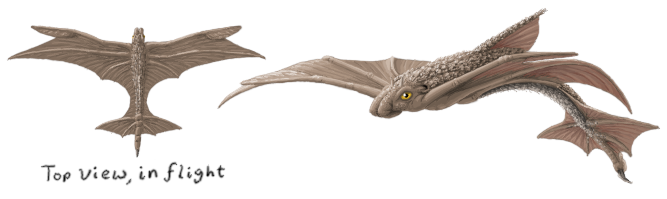

Flit-loops are loopers that have extended front fingers to make an effective wing, and the back toes are adapted into an aerodynamic fluke. Up and down motions of the flit-loop's leg provide propulsion for powered flight.

Flit-loops are more clumsy on the ground, but are agile fliers once airborne.

The same powerful leg that propels them through the air also allows them to leap directly into flight from the ground.

|